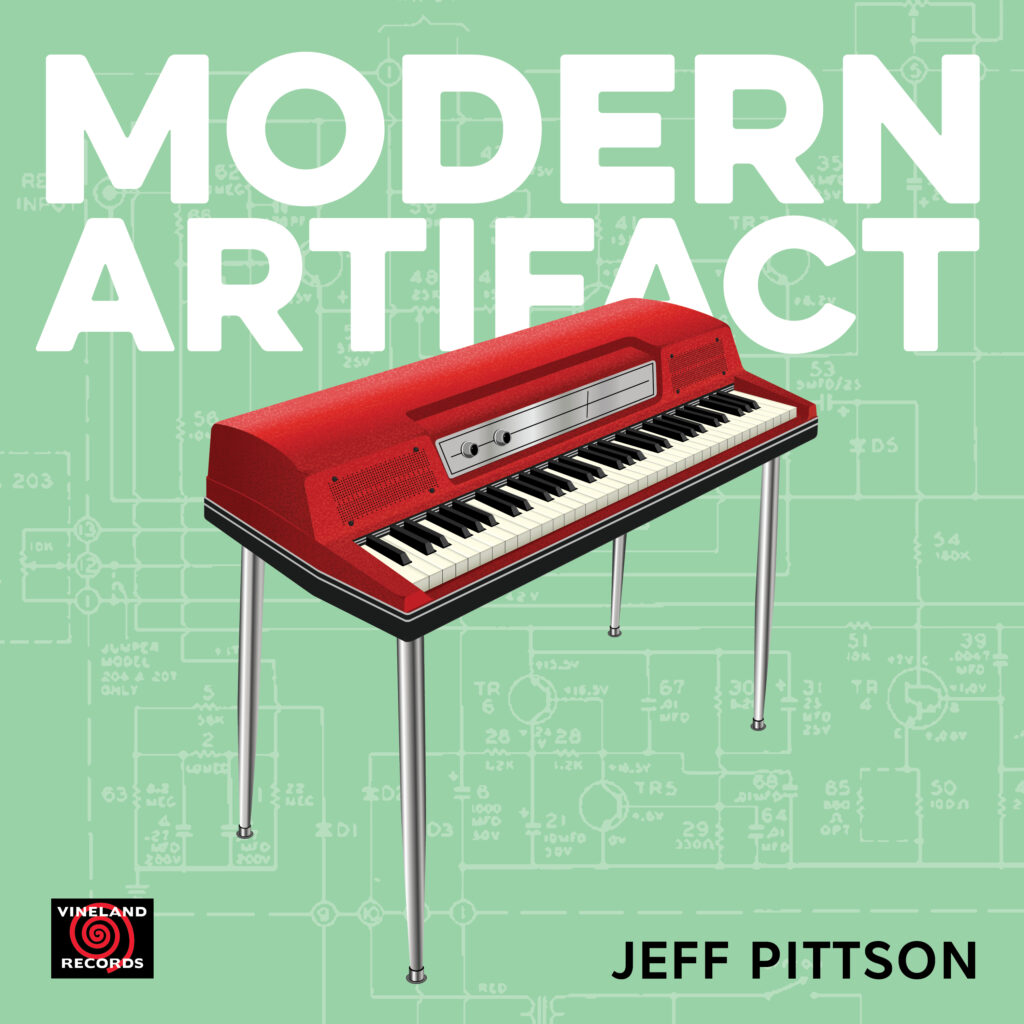

Modern Artifact

1. Solar (Davis)

2. Blue Skies (Berlin)

3. Just In Time (Stein/Green/Comden)

4. The Face of Love (D&T Robbins/Khan)

5. Out of Nowhere (Green/Hayman)

6. Zoyd (Jeff Pittson)

7. Everything Happens to Me (Dennis/Adair)

8. I’ll Follow the Sun (Lennon/McCartney)

9. Ruby (Parish/Roemheld)

Jeff Pittson: Wurlitzer 200A Electronic Piano, with Tel-Ray Variable Delay

Recorded: Sanctuary Sound

San Francisco, CA

December 1999

Mastering: Dave Bell

Bellboy Recording, Richmond, CA

December 2001

Released April 1, 2021

Liner Notes

MODERN ARTIFACT: or “How I learned to stop worrying and love the Electric Piano”

By Jeff Pittson

1959 was the first time I heard the Wurlitzer electronic piano. Later, as an adult, I realized that the AM radio experience of my youth was an especially rich eco-system where jazz, pop, rock and folk music could peacefully coexist on the same station. Hearing Ray Charles “What’d I Say” made me a fan for life and, despite the fact I was just 6 years old and knew nothing about music, the sound of this electric keyboard was like no “ordinary” piano and, what’s more…I liked it! My request for piano lessons at the age of 5 was delayed until I was 10 in 1963, beginning study in September of that year, just one month after my birthday, and five weeks before President Kennedy met his fate in Dallas, Texas.

The Rudolph Wurlitzer Company, commonly referred to as Wurlitzer, was founded in 1853 and based in Cincinnati Ohio. They first enjoyed success through government contracts supplying band instruments to the U.S. Military. After moving to North Tonawanda New York in 1880, the company began producing pianos as well as band organs, orchestrions, player pianos, and theater pipe organs which entertained generations in theaters during the silent film era.

Wurlitzer began manufacturing the electronic piano in 1954 based on a design by inventor Benjamin Miessner of a smaller metallic reed which replaced the strings of a conventional piano. This invention was then co-developed by Wurlitzer with production beginning in 1955 with the model 110, leading to the120 in 1956 and, ultimately, the 200A in 1974. After almost 120,000 electronic pianos, production ceased in 1984.

Fun fact: Ray Charles first brought the Wurlitzer 120 out on the road because of the disrepair he regularly encountered with acoustic pianos in the concert venues and clubs he worked with his band. Photos exist of his band showing the Wurlitzer as the only keyboard on the stage. Regardless of its advantages as an in-tune keyboard, Ray’s sidemen grumbled about the use of the Wurlitzer on the gig, though I suspect, with Ray being both the boss and paymaster, not that much! One fateful night, in a “vamp until ready” scenario, he improvised the immortal bass line and intro groove that framed “What’d I Say” which, when released, became the first use of the Wurlitzer electronic piano in a top 10 pop chart hit.

In the past, purists frequently questioned the very necessity and existence of the electric piano, often in person, and, of course, directly to the musician playing it. To illustrate: in 1978 I played a trio gig at the legendary Keystone Corner in San Francisco and brought my Fender-Rhodes 88 Suitcase piano to the club (complete with anvil cases!) and played it along side the 7’ Yamaha grand. On a break, a patron come up to me and remarked that while he enjoyed my playing, he asked, “Why-oh-why are you playing “that toy piano”? Or did he say, “play” piano”? Argh! I wish I had replied to said twit, “If it’s good enough for Bill Evans…that’s why!!” Good talk.

Purist condescension aside, history has recorded, quite literally, a wealth of magnificent, and yes… even breathtaking sounds that have emanated from many different models of electric pianos crossing a huge spectrum of music. In 2021, keyboardists regard these instruments as yet another set of colors, or artist’s brushes, valid in and of themselves and enhancing one’s performance options. Ray Charles could have recorded “What I’d Say”* without a Wurlitzer Model 112, but the song would not have had the unique bite of that instrument and that resulting thing called soul. One can assert without fear of contradiction that “In a Silent Way” and “Bitches Brew”, two of Miles Davis’ greatest post-acoustic quintet albums, would not exist without the tone-color of the Fender-Rhodes piano and the exotic and other-worldly sonorities that Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Joe Zawinul and Larry Young conjured up for the sorcerer himself.

In the electric piano wars, prior to the disruptive technology of FM synthesis inside the 1983 Yamaha DX-7, the Rhodes certainly won out, becoming the dominant electric piano in jazz and pop music. With its sturdy construction, tuning stability, and ability to travel well, one could lug it to and from a venue where the piano was unplayable, of dicey pedigree, or non-existent, again supporting Ray’s reasoning but with the Rhodes as an even heavier instrument. I have vivid memories of Mark Isham, pre-Hollywood film composer fame, graciously loaning me his Fender Rhodes 73 Stage Piano for a certain gig. I just had to haul it up and down a narrow, rusty and rickety, three story Victorian wrought-iron circular staircase in San Francisco’s beautiful Noe Valley district! No mean feat as it weighed nearly 100 pounds with legs and pedal stored inside its lid! Ah…the memories of intrepid youth and a stronger back.

Despite the Rhodes dominant status, the Wurli has one big advantage over its rival: it possesses a delightfully light, tactile and responsive action which enables one to fully express, as nearly as possible, what is in your head when improvising. To wit, it was the inimitable Art Tatum, who, following a respectable club engagement on 52nd Street, would then venture uptown to some small “hole-in-the-wall” joint to play a lowly spinet or upright. Why? Because he liked the action. Glenn Gould has said, and I paraphrase, “Give me a light action and the sound will take care of itself.” The example of Messieurs Tatum and Gould offer compelling support for the primacy of a light action.

Electric pianos I have Loved: I first played the Wurlitzer electronic piano, most likely a model 200, after my initial teenage experience with the Fender-Rhodes at Whitney’s music store in downtown San Francisco circa 1967. At Sherman-Clay, the music store where I later took lessons on Hammond organ with Tom Coster, I remember a brief but enjoyable encounter with a wooden cased Hohner Pianet N, with it’s unique, and lightning fast, sticky pad action. Fantastic feel but there was no sustain pedal! That funky sound was made immortal by Rod Argent in The Zombies hit “She’s Not There”. The Wurli, in contrast to the Rhodes, had a more responsive action which I liked immediately as opposed to the routinely more sluggish Rhodes which required considerable service to make quicker. Later I discovered several other Wurlitzers: the first solid state model Wurlitzer 140, a tube amp model 120 and later, while teaching at Sonoma State University during the 1990’s, I prevailed upon the music department to dig out of storage,and place in my office, a Wurlitzer 203 which greatly resembles the original Fender Rhodes Suitcase piano, complete with keyboard resting on large lower cabinet-amplifier with built in sustain pedal! A very rare item.

While I’m not certain if “Modern Artifact is the first solo Wurlitzer album,if it is I would be happy and gratified. Having finished the recording, I realized that I had not once used the idiosyncratic built-in vibrato (in reality a tremolo with a single speed and no pitch variation) at all. In retrospect, it tended to conflict with what I was trying to project musically even though I am fond of that particular effect. What I did use was the Bomb Factory Pro Tools plug-in which authentically models the beloved and increasingly rare Tel-Ray oilcan reverb. The oil-can reverb has a tangible vintage vibe to it, complimentary to the Wurlitzer and the era in which it was produced. I love the ambience it provides…a dark,subtle and diffuse wash of sound surrounding the Wurli. In a word…delicious. A bit of urban/musical mythology debunked: the original Tel-Ray unit, with its signal modifying oil sloshing around inside a sealed can, was never carcinogenic as reported. The ProTools plugin reverb, courtesy of Dave Bell, is an uber accurate model of that now, mostly lost, reverb device.

Regardless of the brand, type, or vintage, modern musicians continue to record, perform and practice with this timeless modern artifact, an electro-mechanical animal born of another era. Even as decades pass, they remain welcoming and attractive with their subtle touch response variations, imperfect beauty and subtly distorted analog output. With a mechanism (tines,reeds,bars) that vibrates in real time and put into motion by a skilled human hand, that epoch remains an esthetic to be cherished and appreciated. An expressive vibrating musical instrument played by striking a key which impels a felt covered wooden hammer to strike a metal reed: variations on the time honored piano building paradigm. Fabricated, adjusted, repaired and played by human hands. In an ever expanding digital world, is this not rare and wondrous? A big thank you goes to Al Molina for selling me my personal instrument and Brian Melvin for the extended use of his AKG microphone. With 64 notes and a sustain pedal, the Wurli is the very model of outward simplicity with just two knobs on the front panel: on-off/volume and vibrato. That’s it.

This recording was done on a mint condition Wurlitzer electronic piano, model 200A, manufactured in DeKalb, Illinois, serial number 87239, with an AKG stereo condenser microphone, with direct input to a Sony Minidisc recorder, model MDS-JE630.

Mastered in ProTools by Dave Bell, Bellboy Recording, Richmond CA.

I sincerely hope you enjoy it.

Jeff Pittson

April 2021